But Why Are You Making Me to Get Mad What Have I Don Gwrong to You Baby Do You Want Tokill Me

Trigger warning: This story explores suicide, including the details of how the author's mother took her own life. If you are at risk, please stop here and contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support. 800-273-8255

I stood and looked down into the canyon, at a spot where, millions of years ago, a river cut through. Everything about that view is impossible, a landscape that seems to defy both physics and description. It is a place that magnifies the questions in your mind and keeps the answers to itself.

Visitors always ask how the canyon was formed. Rangers often give the same unsatisfying answer: Wind. Water. Time.

It was April 26, 2016 – four years since my mother died. Four years to the day since she stood in this same spot and looked out at this same view. I still catch my breath here, and feel dizzy and need to remind myself to breathe in through my nose out through my mouth, slower, and again. I can say it out loud now: She killed herself. She jumped from the edge of the Grand Canyon. From the edge of the earth.

I went back to the spot because I wanted to know everything.

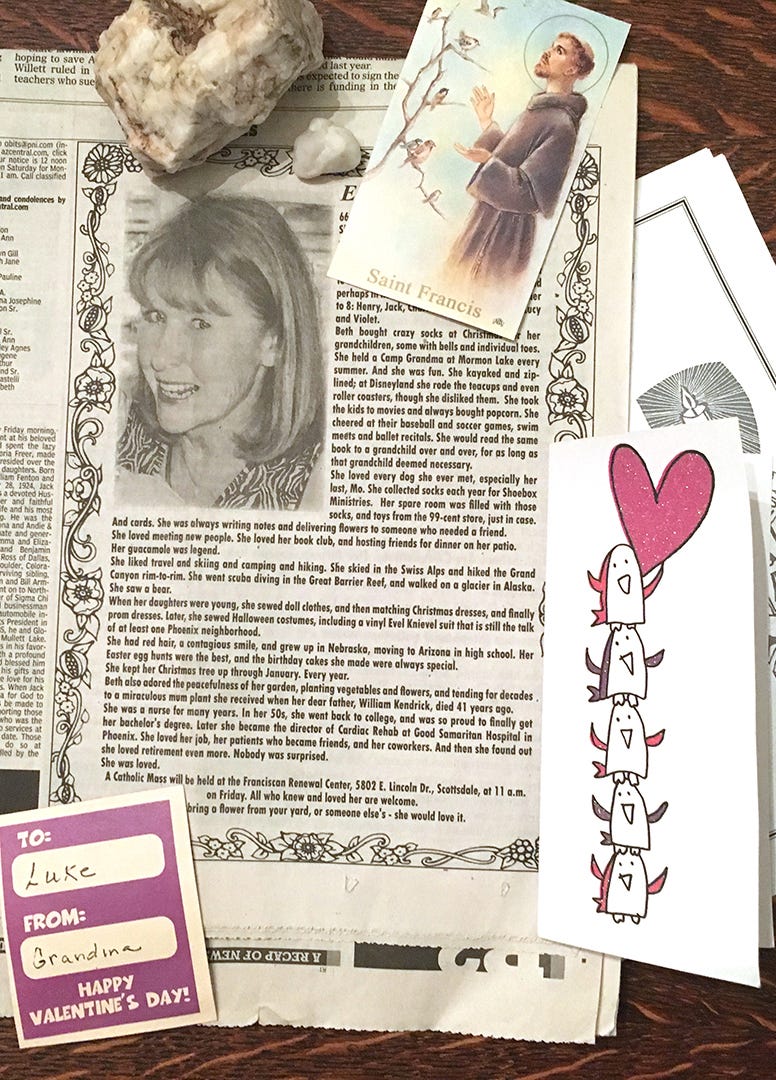

The latitude and longitude where she landed, the last words she said to the shuttle bus driver who dropped her at the trail overlook, her mood when she met with her priest just four days prior. I read over the last letter she had mailed to my children. I looked for clues inside this little card with a cartoon penguin drawn on the front, written in block printing so my 5-year-old daughter could easily read it. My mom wrote of riding the Light Rail to a Diamondbacks game, of planting a cactus garden, of looking forward to summer in the already hot days of a Phoenix spring.

I read and reread her last words written in cursive in the tiniest composition book that she had left in her Jeep, as well as the last text she typed, in which she both celebrates life and apologizes for it. I zoomed in on the photo she took with her iPhone from the ledge looking out to the sunrise that lit the canyon that morning to see if the rocks or shadows would share anything new. I replayed our last conversation, and each one before it that I could remember.

I wanted to know every fact, every detail, to see everything she saw, because I didn't have the one thing I wanted – the why.

I came back to the canyon for answers, or a deeper understanding of life and my mother, or maybe myself. But all I could see were the peaks miles away, the trees greener and prettier than I imagined, tiny dots of figures moving slowly up the switchbacks, and the stillness of the world.

Suicide is as common and as unknowable as the wind that shaped this rock. It's unspeakable, bewildering, confounding and devastatingly sad. Don't try to figure it out, I told myself, stop asking questions, assigning blame, looking.

Yet there I stood, searching.

• • • • • •

The morning she jumped, she tried to reach me.

I saw "Mom" pop up on my phone shortly after 10 a.m. I was sitting at my desk on the 19th floor of the Cincinnati Enquirer building at a new job as the managing editor I hadn't quite settled into yet, just one photo of my children on my desk.

I quickly texted: "I love you mom. Crazy busy work day. Hard to break away to talk. But know I love you."

On my short drive home that night, I smiled when I noticed the iris were starting to bloom in our neighborhood. I stopped the car, hopped out and took a photo of an iris to text to my mom later. It was our favorite flower – hers because of the tenacity they need to grow in the rocky mountainside where she lived, and mine because when I was a kid, they bloomed for my birthday.

I might take more after my dad; I have his olive skin and eyes that are so brown they are almost black, his look of quiet disdain when I am angry and his need for popcorn at the movies. But I was closer to my mom.

We lived 3.3 miles from each other for most of my adult life. Sometimes she would stop by to see my kids, and we would rub each other's hand while we talked about the day. When I moved to Ohio recently, we talked on the phone every day.

We could make each other laugh, and sometimes it seemed whatever she felt, I did, too.

That night, my husband said he needed to talk to me. "Come upstairs, and let's sit down."

I put a lasagna in the oven and walked upstairs and sat on our bed.

We'd been fighting. We had moved from my hometown of Phoenix to Cincinnati three months earlier, and it had been a rough transition – a new city where we had no family, four kids in new schools, a house where the rent was too high and we seemed to be saying too often, "Can you wait until next Friday?"

He looked serious.

"It's your mom," John said.

And somehow I knew. He read my face.

"Yes," he said. "She's gone. She was at the Grand Canyon. … They found her body in the canyon."

He used the word body.

I couldn't think, couldn't process order or time, and I took John's T-shirts out of a drawer to re-fold them.

"We need to tell the kids," I said.

I started to cry in a way I wasn't sure I would ever stop, in a way that I was no longer aware that this might scare the children.

Henry and Theo would understand this. They were 13 and 11, smart and mature. But Luke was only 9 and wouldn't even talk about the move. And Lucy was 5 and missing her grandma so much that every night she looked at a photo book my mother had recently made for them.

We came downstairs and found them waiting in the dining room, they knew something was up. My face was red and my eyes wet and swollen, which wasn't new, but part of who their mother had become lately. I sat on the wood floor leaning against the wall, pulling my knees to my chest. Lucy sat closest, and they formed a row next to me along the wall.

There was no way around this, no way to tell this.

"Grandma died," I said. "I'm so sorry."

Luke and Lucy crawled into my lap. Henry looked afraid. Theo asked what happened.

"Her heart stopped working," I said. It was true, it did stop working. We would tell Henry and Theo the rest later, in private.

I started to cry in a way I wasn't sure I would ever stop, in a way that I was no longer aware that this might scare the children. John called my psychologist, and although she worked 9 miles away, she happened to be at a church four blocks from our house. When she got to the house, I told her I was to blame.

"No," she said. "Your mother made this choice."

The lasagna, I remembered. I yelled to John to take it out of the oven.

"Laura," she said, "this is not your fault, not your doing."

But maybe it was. The letter, I thought. I should not have sent that letter.

Three days before, I had written an email to my mother. It was a letter I had written and deleted and written again. It talked about things that I'd hidden for years, things I was finally trying to make her see. It doesn't matter, I told myself. It doesn't.

She is gone. She's gone because she wanted to be gone. But did I push her?

NEWSLETTER: Personal updates from the writer and more on Surviving Suicide

Counting backward

Looking for answers after my mom's suicide

Reporter Laura Trujillo returns to the Grand Canyon, where her mother died by suicide, and reckons with "the great unknown."

David Wallace, Arizona Republic

A few months before my mom died, in the fall of 2011, I sat in a Phoenix office with a psychologist, the first time I'd done one-on-one counseling. I don't know what's making me sad, I told her.

We explored work. I loved my job working at my hometown newspaper. We explored family. I had a great husband and four wonderful kids.

Then childhood. It was good, I told her. It was good, the bad couldn't take away that part. It was good, I said again, until slowly, the truth unraveled. The details came out one at a time, like from a leaky faucet, steady at first and then faster.

I was 15 when I saw my stepfather naked.

Not because I was looking, but because he wanted me to see.

He came into my room. Not because he needed to.

He told me not to say anything.

And I knew I wouldn't. My mom was happy for what seemed to be the first time in her life. I couldn't ruin that, I told myself, no matter what he did to me. Close your eyes, count backward from 10. And again until it is over.

Push it to a corner of your brain. Shut the box.

For years my stepfather raped me to the point that I questioned whether it was my fault. One day it stopped almost as quickly as it began, and I blocked it from my mind for decades. I told no one.

I went to Sunday dinner at my mom's house, camped with her and my stepfather in their motor home in Flagstaff, and took care of their yellow Labrador, Moe, when they went skiing. I pretended it never happened until one day I couldn't.

After a few appointments with my psychologist, I told my mom one evening in the front yard when she had stopped by my house. That day she didn't say she didn't believe me, but she didn't seem surprised. She didn't reach over to hug me, didn't ask how, didn't say she was sorry. She went home to him.

I struggled to understand how she didn't seem to want to know more, didn't seem angry with him, didn't seem to do anything about it. I was angry and sad in a way neither of us knew how to handle.

We're not supposed to blame ourselves when someone we love kills herself, but often do anyway. What if I hadn't moved away? What if I'd kept quiet about my stepfather? What if I had answered her phone call that morning?

For a while we ignored the subject altogether. But slowly her denial gave way, and she started asking questions. She wanted to know how the man she knew, the one with the gentle heart who hired a homeless man to work in his bike shop, could be capable of this. We went days without talking, then talked until we both couldn't breathe from crying.

One night, maybe a month before she died, while she and I talked or mostly cried on the phone about how sorry she was and about how much it hurt me and how sorry I was and how much I missed her and needed her, she confronted him. I could hear her yelling at him with me on the phone: Did you do this? He kept saying, "I don't remember. I don't remember." Maybe he didn't, couldn't. She was angry, yelling at him: "Why did you do this?"

Her husband was 66 and sick. He drank a lot, and a brain tumor and stroke left him dependent on her. My mom and I had been circling each other like wounded animals, each apologizing to the other, for a few months when I wrote and deleted and rewrote the letter and finally hit "send." It didn't tell her anything she didn't know, but it spelled out that he had abused me for years, how hard it was to have him come into my room so many nights, and then there was this: I didn't tell her then because I wanted her to be happy. I told her I didn't forgive her, because I didn't need to. It wasn't her fault. I told her I loved her and needed her.

We're not supposed to blame ourselves when someone we love kills herself but often do anyway. What if I hadn't moved away? What if I'd kept quiet about my stepfather? What if I had answered her phone call that morning?

The "what if" question held me the tightest at night, keeping me awake until the sun peeked through the shades.

I needed to know if I was to blame.

My mom was a retired nurse and hospital administrator with a good pension. She had a book club and friends she hiked with weekly. While she hated that four of her grandchildren had moved so far away, she had four more who lived close and plans to visit the others soon. I needed to find out what I had missed. I needed to know, to understand how someone who seemed so happy could be so sad.

I'd comb through my mother's life, looking for clues. I'd learn that she had been seeing a psychologist and had been prescribed antidepressants. I'd talk to my sister, try to ask questions of my grandmother and aunt, and I'd drive 966 miles to Florida to spend a week with my mom's best friend from when I was a child.

I'd learn everything I could from doctors who study suicide notes to psychiatrists who personalize medicine to treat depression. I would learn that suicide is now the 10th-leading cause of death in the United States, with numbers increasing in almost every state, and that money for research to better understand it remains low. I'd explore the ugliness inside my own family and the ripples of sexual abuse.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Why we're sharing this story

SUICIDE PREVENTION: It's one of the nation's top killers. Why don't we treat it like one?

The funeral

The day before my mom's funeral, the church was quiet. It was May and already 100 degrees in Phoenix. I walked past the meditation chapel and through a healing garden and rock labyrinth to find the priest that my mom had been talking to the past few weeks.

He had a trim white beard, a bald head and round wire-rimmed glasses. He couldn't tell me what he had discussed with my mother but that she told him she thought she no longer needed counseling.

I had learned that when some people decide to kill themselves, they seem more at ease than they have in a long time, because they know that if they show any suicidal signs or too much distress, others will try to talk them out of it.

My mom believed in God. I sat down and asked if my mom was OK. I thought he could explain.

Instead of answering, he told me a story about his own mother who had died and how on an autumn day a few years ago he was lying in a hammock and he saw her again.

He was just a man in a Hawaiian shirt and Birkenstocks telling me a story.

I wanted a new priest. I wanted someone to tell me my mom was OK.

My sister and I had talked and agreed on a few things: I would write the obituary, our mom would be cremated, the service would include a full Mass. We called it a Celebration of Life, as if there was such a thing in the moment.

They thought she wasn't strong enough to hear it. And maybe she wasn't.

One of my mom's favorite places was her garden, so we asked that friends bring flowers from their yard or someone else's. Roses and mums, prickly lantana and yellow branches of the Palo Verde lined the church. Lucy held Fred, a stuffed dog that was recently handed down to her by her biggest brother. Luke held Henry's hand.

I wanted to ask my grandmother what happened, what she knew, the parts of the story she understood, her truth. Not right then, maybe later that week. But when I saw my grandma, she looked at me, my husband and our four children and she waved us off.

She blamed me, I learned later, as did my mom's sister and brother. My mom had told them I had told her about the abuse and she was upset. They thought she wasn't strong enough to hear it. And maybe she wasn't.

Ten minutes into the service, my stepfather walked in.

At the funeral I told stories of my mother, how she never wanted anyone to be cold, how she would knit caps for her grandchildren when they were babies, even in the summer, of how she collected socks for the homeless so their feet wouldn't be cold.

It was 34 degrees the morning she was found. She had on a lightweight jacket.

"Mom," I told her, "you weren't alone. You weren't. And I hope you were not cold in the end."

As each person left the church, my mom's best friend handed them a piece of dark chocolate, my mom's favorite treat. It sat in my mouth taking forever to dissolve, like a communion wafer.

A close call

For a while, Henry, Luke and Lucy each received a note from my mom in the mail. After we moved, she had sent cards and stickers, silly presents from the dollar store like stretchy rubber bunnies and colored beads, clutter that got caught in the vacuum cleaner, that I simultaneously loved and hated.

Theo checked for weeks for a last letter that never arrived.

I was angry at myself for not mailing all of the letters my kids had written her in the past weeks. But I didn't have a stamp or was in a hurry. I wondered if those notes would have sustained her until her pain could lift, medicine and therapy could work, or the burden of caring for her husband, who would die three months later, would pass.

There are researchers who will say that putting the onus on survivors is grossly unfair, that we need more money to understand suicide, to learn what works so we can do better.

They will say to look at how mental health screenings from primary care doctors or more training for therapists could reduce suicides. There are people who will say that a prevention measure such as a net or barrier could have saved my mother and that such measures buy more time for people to change their state of mind. They're all good things to think about, worthy places to direct anger or energy. But I spent most of my time looking inward.

Sometimes there were periods when all I could feel was her absence. I could look down at my knees, which wrinkle and bend in the same way as hers. But it wasn't her. I wanted to go be with her.

The summer after she died was the most difficult. I was working and taking the kids places and making dinner most nights, but even when I smiled or laughed, I was empty. I pretended I was fine, posted happy photos of my children on Instagram, and thought if I told friends that I was OK often enough it would be true.

Once a week, I ran 9 miles for the empty space, but all it did was give me time to think and wonder why. I would tick through the list of reasons why logically I should be happy. But something in my brain wouldn't let me get there.

I went to counseling and lied to my therapist, saying the things I thought she needed to hear. I couldn't look her or anyone else in the eye and say I no longer wanted to live, even if it was true. I was afraid to say it out loud. She prescribed me antidepressants, which I reluctantly began to take.

It's a common feeling, this depression after losing someone to suicide, yet it often feels impossible to share. It's raw and scary, and sometimes it feels selfish or indulgent. My mom wasn't a child; she was 66, an adult who made her own decision. And yet it consumed me.

Most of the time, as in the obituary that celebrated my mom's life, I neglected to mention how she died. I didn't want to tell people about my mother. Her suicide was not a secret, but it was a wound, and talking about it allowed people dangerously close to the darkest parts of myself. I didn't want to tell people that I had decided I didn't belong here anymore, that I had removed my seat belt while driving and sped toward a concrete wall underpass, jumped up to see if the pipes in our basement were strong enough to hold me or that I had fallen asleep hoping I wouldn't wake up. I didn't want to tell anyone that I had written notes telling my family goodbye.

Death seemed the only answer. One afternoon in the summer after she died, I took off work and bought a one-way, same-day plane ticket to Phoenix. I wanted to be with her in the canyon.

Maybe we all are one step from the ledge. I couldn't understand it until I could.

It scared me.

Death seemed the only answer. One afternoon in the summer after she died, I took off work and bought a one-way, same-day plane ticket to Phoenix. I wanted to be with her in the canyon.

I was crying. I told the kids I just needed to leave, to get out of the house for a bit. I was certain they would be better off without me. Theo handed me a note, I slid it in my purse without looking at it. I drove away.

I got almost to the airport, and I pulled over into a parking lot. I was crying, and even though I wanted to die, I knew I couldn't drive, I couldn't go home, I couldn't be.

I read Theo's note, handwritten in a thin magenta Sharpie on a 3-by-5 index card: "I know U love me and I love U Theo."

I could not do this. I saw my mom in Lucy, in her profile, in her eyes, the way she stood.

I went home.

Truth

I have learned, as do many survivors of a family member's suicide, that I am now at risk. I accept that now and guard against it. It's a place of caution and checklists. A place where I know to not stay alone in my head too often and to say "yes" to walking the dog with my best friend.

Years of therapy, antidepressants and luck have led me here. There was no aha moment with my psychologist, no time when everything suddenly felt clear, no moment when my guilt disappeared. Instead there was more a dull monotony of months of sessions talking through my worries and what ifs, and the reasons I shouldn't have them, until they slowly dissipated. I carried Theo's note in my wallet and later put it on my dresser to see each morning. In the worst times, I had friends who texted just to check in and a husband who knew to send a kid with me on errands so I wouldn't be alone. And with medicine, I now had the sense to listen.

LEARNING TO COPE: Self-care tips in suicide survivors' own words

It took four years to tell Lucy the truth. I picked her up from her friend's house on my way home from work. It is a distance of 26 houses and two left turns.

She looked at me, this time as a 10-year-old, so much more grown up, not suspicious, not quite serious, just honest.

"Tell me really," she said, "How did Grandma die?"

When I told her, Lucy looked sad and angry together. She got out of the car, dashed up the stairs to her room and slammed the door.

I knocked.

"Go away," she said. "You're a liar."

I wanted to say so many things: How much her grandma loved her, how my mom adored Lucy – her first granddaughter after six boys. How my mom used to make Lucy a special doll cake each birthday. How much I missed her and how much it hurt me. How I squinted and tried to figure out how many of those times that my mom stopped by our house with a beautiful smile and a hug when she wasn't happy, that she must have been hiding it and I missed it.

But when she came out, maybe 20 minutes later, she just needed a hug.

"I don't want you to do this," she said. She didn't look up at me.

"What? Do what?"

"Promise me. Just promise you won't do this?"

"What do you mean, Lucy? Just tell me."

"What Grandma did." she said. "Please don't do it."

I've decided that I need to live, not just for me, but my for children. I know what it felt like to be left behind.

The great unknown

There remained a yawning uncertainty. And questions, so many of them, about my mom.

My mom first saw the canyon when she was an adult, a visit with her sister shortly after she and my dad divorced. Later she hiked rim to rim with her sister – 23.5 miles from the North Rim of the canyon and back up the south, a hike that is revered in Arizona, a point of pride – the equivalent of a 26.2 oval sticker on the back of your car. She hiked the last time with her husband, taking the easiest trail as his knees started to give out.

The year my mom took her life, 12 others died at the canyon, too – falls, heart attacks and suicides, mostly. Enough people die at our 58 national parks that the U.S. Forest Service has created a special team to deal with death. They are there to investigate and understand, to find the next of kin, to provide information and some context where there might not be any, and sometimes simply to stand quietly next to you.

Ranger Shannon Miller agreed to meet with me at the canyon four years to the day after my mom jumped.

Will you be alone? She'd asked me.

No.

Good.

Nearing four years after she killed herself, a friend and I drove to the canyon from Phoenix at 1,000 feet above sea level, as a storm moved in and the sky darkened. It's just over a three-hour drive, a straight shot north on I-17 through the Sonoran Desert and then the Coconino and Kaibab National Forests. My mom would have made this drive in the middle of the night or just before dawn. As we gained altitude, the saguaros gave way to scrubby bushes and later to ponderosa pine trees at 6,900 feet. Mule deer and elk dotted the roadside. By the time we reached Flagstaff, about 90 minutes from the canyon in northern Arizona, it was snowing and the temperature had dropped more than 55 degrees.

It is a long time, Mom, to change your mind.

Shannon and I agreed to meet at Bright Angel Lodge, where you can pick up a permit to camp at the canyon's floor, reserve a mule to carry you down the trail, and stop in the gift shop to buy an "I hiked the canyon" T-shirt, a toddler-sized ranger replica uniform, and a dream catcher made by Native Americans for $26 or one not for $1.99.

In a row of books, the tales of the Harvey Girls and hiking trails, rafting and geology, I found something: "Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon, Gripping accounts of all known fatal mishaps in the most famous of the World's Seven Natural Wonders." It boasted: "Newly Expanded 10th anniversary edition." A placard reads: "Gift Idea!"

I picked it up, glancing around to see if anyone was watching. There was the story of John Wesley Powell, the first to explore the river cutting through the canyon, and the TWA and United airplanes that collided over the rim in the 1950s and led to the creation of the Federal Aviation Administration.

I flipped through, and on page 470, I found her.

My mom.

I put it down.

Shannon met me in front of the lodge, and I followed her truck to the spot where they found my mother.

"Ready?" she asked me. She had that just-right mix of ranger and detective, and her smile felt like a hug.

We walked down a concrete path along the canyon, juniper trees on the left, a ledge and waist-high metal pipe handrail on the right. I could see a short fence and jagged limestone that formed an overlook. When we neared the spot, Shannon pulled yellow caution tape from her bag and cordoned off the trail.

"You might want some quiet," she said.

I looked around, worried how this intrusion could ruin someone's view on their only trip to the canyon. She reminded me that there are many places to see the canyon and for now, this was my spot.

I looked around, worried how this intrusion could ruin someone's view on their only trip to the canyon. She reminded me that there are many places to see the canyon and for now, this was my spot.

"It's better this way," she said.

This spot along the 277 miles of canyon is known for one of the best views from the South Rim. The limestone here on the Kaibab layer is 270 million years old. It's the youngest layer of the canyon, an area that once was covered with warm, shallow sea. Its name is Paiute Indian and means "Mountain lying down," and somehow I like that image. It makes no sense and yet is perfect.

The rock at the bottom – the vishnu schist – is 2 billion years old, half as old as the earth. Shannon talked volcanoes and rivers, snow and dry wind, tectonic plates and tributaries widening the canyon, about how native people roamed this area for thousands of years.

Up until 1858, when John Newberry was the first scientist to reach the canyon floor, the area was called the Great Unknown. And even with as much as we know, there is still some debate as to how the canyon formed and the Colorado River's relatively new role in it.

Holding onto the rail, I peered over, looking down, farther now, to a second ledge about 100 feet below. There were pine trees and a pinon, scrubby brown earth and openness. It looked like a shelf.

"There?"

"Yes, there," Shannon said.

"It looks different," I said. Just 100 feet down, it already was a different terrain with different dirt and plants.

It's the Coconino layer, Shannon explained, a layer that formed 275 million years ago. The light sandstone forms a broad cliff. The lines you see in this layer, the cross-bedding that run through it, reveal the story of an area that used to be covered with dunes, the wind blowing them into shapes, over and over again. It appears there are waves within the rocks.

I got lost in the geology for a moment, standing in a place that held rocks 2 billion years old, and my brain placed the two and six – no, nine – zeros to the right. That is not forever but an amount of time I could not understand.

I focused on the facts. The trees and rocks, how the Colorado river snaked below almost exactly 1 mile down into the earth, the sound of a raven and the light rain that was slowly growing heavier and turning to snow.

My mom fell 5 million years.

"It's cold."

That's all I could say.

Trying to understand

Jean Drevecky drove the Paul Revere shuttle bus that fourth Thursday morning of April, 2012. She would later tell the rangers that during her first round that morning she picked up a woman near Bright Angel Lodge who seemed calm. That woman was my mother. Jean remembered the woman sat alone, quiet, her hands in her pockets "like she was cold." The woman got off the bus five minutes later. Phone records show that my mom called her husband several times that morning. He remembered only the one that came at 6:56. It lasted four minutes. She was crying.

She told him, "This is it. I am finished I cannot go on."

Her husband told rangers he tried talking to her about all of the good things in life. The ranger report doesn't detail what he meant by that, but they had scuba-dived the Great Barrier Reef and taken a hot air balloon above Albuquerque, New Mexico. He found the adventurer in my mother, but he broke her, too. He broke us.

She did not say goodbye.

"Your mom must know this place pretty well," Shannon said, noting that of all the miles of canyons here, my mom knew the place to jump where she wouldn't hurt anyone else and would be easy to be found.

I was quiet for a moment, for once not feeling the need to fill the space.

I nodded.

"Yes."

I looked down the trail, to the 27 switchbacks I counted until they grew tiny and disappeared into the canyon.

I'd been here before, I realized. With her.

It was the summer after my freshman year of college, from an overlook – this one.

My mom took just one day off from work, and we drove to the canyon on a Friday morning, sharing a double-bed in a hotel overlooking the South Rim. The next morning we woke before the sun to hike the South Kaibab Trail, 7.1 steep miles down.

"Better down than up," she said in the happy singsong voice she used when any of us faced something difficult and that I now sometimes hear in my own voice. I try to remember the details, but only certain things stick out. Are the memories real or only built from photos? I had brought a Walkman that held the Depeche Mode "Some Great Reward" cassette tape. It was 1989, and I would not own a CD player for another three years.

We carried water and salami, string cheese and a peach. I still remember we didn't eat the peach, and the bumpy hike down turned the fruit to mush in my JanSport backpack.

Reaching the bottom, a severe drop in elevation to 2,570 feet, the temperature hit 101 degrees. Near the Colorado River it was as humid as a sauna.

That night we sat in a circle under the stars and listened to a ranger share a story about a mystery on the Colorado River. I leaned into my mom, her hair smelling like Ivory because she washed it with a bar of soap, and fell asleep.

I have a photo of us at the top after hiking up Bright Angel Trail. She is smiling, her hair permed and curly. Mine is pulled up in a ponytail, likely with a scrunchie. It is hard to tell if I am happy or just exhausted. Every picture from the the past gets studied from time to time: Does she look happy? Was she happy? It's just one moment from almost 30 years ago, and I don't have the answer.

How does someone go from happy to suicide? Was she truly happy or did we just miss the clues?

Had she been sick her whole life? Sometime after the funeral my sister and I discussed the day when we were kids that our mom set a fire in a bathroom garbage can. My mom put it out before it spread. Soon after, our grandmother and her grumpy miniature Schnauzer moved in with us.

So the thing with suicide is this: Everyone has their own part of a story, but many won't share. No one has the answer, and sometimes the bits they have, they lock inside. Or they remember the way they can, or want.

After my mom died, we each tried to understand what happened and what we knew. My sister shared that at some point when I had been in middle school, my mom drove to a parking lot after her night shift at a hospital with a handgun she had bought for self-defense. She changed her mind.

My sister said that our grandmother told her that our mother was put in a hospital at some point before she got married, but when I asked my sister later about this she said she didn't remember and no longer wanted to talk about it. My mom's mother, brother and sister don't want to talk to me about my mom's suicide.

So the thing with suicide is this: Everyone has their own part of a story, but many won't share. No one has the answer, and sometimes the bits they have they lock inside. Or they remember the way they can, or want.

And stories change over the years – memory, maybe, or survival. There are parts to this story that we each have but won't share. So none of us can see the contours and texture of this story, this woman, this life. We just have our disappointments, our myths and our guilt.

For four years, I was certain that the last letter my mom wrote had a stamp with the painting of the Grand Canyon on it. So certain that I never even checked, so certain that I couldn't even look at it until one day I did, and the canyon looked shallow. It actually was Cathedral Rock in Sedona, according to the U.S. Post Office. Even facts are our own, as are truths.

When I recently asked my dad about my mom, if he remembered her being depressed or if there were signs, he said he doesn't remember any. "Why don't you let things be, Laura?"

I told him that writing about it might help. Not me, but others.

His wife interrupted.

"You might not know this, but my brother killed himself," she said. "I blamed myself forever. He always called me before he left work to say, 'I love you, sis.' And one night he didn't."

Looking back, she said, that was unusual. "I could have called him," she said, her voice disappearing, "I could have checked."

My sister and I love each other. She is always polite, the one to simply smile when I say out loud what I am thinking. She also is the one who cleaned everything out of my mom's house, the one who claimed her ashes. She is the one who dropped off groceries weekly for our stepfather because she thought my mom would want that. She is the one who was called three months later when the newspapers were piled up in front of the house. Our stepfather was dead.

Things fell on her that weren't easy, and there are stories she keeps to herself.

Piecing together what we had

My mom knew there was a ledge; she would be easy to find. She knew there was no trail below; she wouldn't hurt anyone but herself. She had safety-pinned a tiny piece of paper onto her jacket with the name of her husband and his phone number. I wonder if the ranger is telling these details to make me feel better. I have a notebook and a pen, and we speak without emotion. This is better, I decide. I am a reporter learning the story. But I am also her daughter, trying to find answers.

"We have people not as courteous as your mom," she tells me.

The first call to the park that April morning came at 7:15: A woman was threatening suicide. My mom had called her husband, telling him that this was it, she was ending it all. She told him she was at the canyon. He called the police, who alerted the National Park Service. Three rangers quickly searched 12.2 miles along the South Rim. By 10:45 a.m., as the weather cleared, the rangers launched a search helicopter. Within 15 minutes, they spotted her body.

Two rangers hiked down Bright Angel Trail and cut across the canyon where they walked another half-mile to reach my mother. They recorded the location.

The ranger zipped my mother's body into a bag, and that bag inside another. Because the winds were too strong, they couldn't fly her out that day, so he secured the bag to a skinny pine for the night. The temperature dropped to 28 degrees.

The next morning the same ranger hiked back to her body and waited until the same helicopter hovered overhead and dropped a basket. By happenstance, my friend Megan had hiked to the bottom of the canyon that morning. She saw condors, rare to see at the canyon, swooping close to the rim.

Watching the birds, she almost didn't notice the helicopter. But hikers know what a helicopter means when a basket hangs below. People paused their hikes. Some crossed themselves and prayed, Megan said, or stood quiet. She didn't know who was in the basket. The helicopter was the only sound.

There were so many signs. It's easy to see them now.

I learned later that my mother had told my sister she was staying at my grandmother's house and told my grandmother she was staying at my sister's house. They both had been worried, checking on her daily. My mom told her sister that she wanted to "walk in front of a truck" and had told my sister she had been going to therapy, as she felt responsible for bringing her husband into my life.

Earlier that week my mom had stopped to see her mother and given her one of her favorite turquoise necklaces that she made, looping a tiny silver heart into the clasp. We would learn that she had also recently moved her house into a trust for my sister and me and written her financial information and passwords in a green notebook. At the same time, she wrote letters full of hope and sweetness to her grandchildren. She went to Mass and talked to her priest.

While researchers say most suicides are more impulsive, my mom's seemed to have left an obvious trail. She was feeling helpless, carrying blame, putting her affairs in order, giving away possessions. But it didn't look that way to any of us at the time.

Despite all of the research, there still isn't a proven formula that can predict precisely who is going to kill themselves and who won't; which interventions work for everyone, or work for a while, and which don't; which words might save someone one day only to have them slip away the next. It doesn't make any sense why one person who demonstrates all the risk factors lives and another kills herself.

The only person who can explain is gone.

So we are left to guess, to piece together what we had. None of us had all of the pieces. The wreckage of my stepfather's behavior had left our family in a state of strain. We weren't sharing information or being honest with each other as we might have in smoother times, which made us normal.

Something the priest had told me stuck with me: "All families are difficult," he said. "Some families just know it, and others don't."

She parked her white Jeep Liberty in the parking lot near Bright Angel Lodge. She wrote notes to her family in a tiny black and white composition book with her name handwritten on the front.

In one, she wrote, "Please don't try to find blame. … I have been sick for a very long time and didn't take care of me."

To me, she wrote: "I can never make things right & no matter what I say or do you will never believe me. Maybe now you can get on with living. You have so much to live for and your family needs you. I do too. … Be kind to yourself. Love mom."

The arc of time

My kids have learned in their own ways to try to understand how their grandmother ended her life, as well as how she lived it. Henry, my oldest who even as a teenager would drop everything he was doing when my mom would stop by, smiles when he talks about her. Now a college junior, he still has a wallet-sized card she made for him when we moved, a photo of her yellow Lab on it and a handwritten note, "Always remember, Grandma loves you. Call me any time."

Theo, who was just old enough to understand how she died, is now a high school senior and the one who sometimes shares stories about her that even I don't know: how she made chocolate chip cookie bowls for ice cream when he stayed the night at her house, or read "The Hunger Games" along with him when he was little, worried he might need someone to ask questions.

Luke still doesn't talk much about her, but as he learned to drive this past summer, he teased me that I drive exactly like my mom: slow and deliberate, with the radio turned down, and I say the exact phrase she would say to me: "Drive carefully. You have precious cargo."

Lucy talks about her frequently with a deep sense of closeness or connection that can surprise me now that my mom has been gone longer than she was here for Lucy. When I opened Lucy's locket, it had a photo of herself in it, which made me laugh. Until I saw that the photo on the other side was my mother. She always wanted them to be next to each other.

• • • • • •

There are days in the years since my mom killed herself that it has felt as if the canyon was everywhere: An OmniMax theater, a school assignment on national parks, vacation photos on Facebook and on the nightly news. Suicide, it seems, also is everywhere: A friend's son took his own life, as did the mother of a former co-worker. A friend shot and killed himself. Another friend told me his mother had killed herself when he was just 12, and for 40 years he has never told anyone but his wife. One celebrity after another dies by suicide, their faces dotting the news.

COLUMN: Media coverage of suicide must go beyond celebrities

I have read and re-read the last text that my mom sent that morning, the one that said her eight grandchildren had been the joy of her life. "I will miss you and seeing you grow to be beautiful adults. I'm so sorry I disappointed all of you, in my heart I know this is not right, but it's all I can do. Pray for my soul."

I have spread her ashes in many places she loved, from the highest hills in Corsica to this very spot at the Grand Canyon.

And on a late summer night this year, after I walked the 197 steps from the shuttle bus stop to the point at which my mother jumped, after I learned every detail down to the height of the railing, I returned to the canyon with my daughter.

On a night without moonlight, you can just see a blanket of stars, more stars than sky it seems. At night the canyon is just a deep, dark hole, and in some ways it feels more impressive than in daylight, the emptiness of it all.

Just as the canyon is so unknowable that geologists and scientists can study it, but will never know exactly how it began, the same is true about my mom. I'm figuring out how to be OK with that.

I think of her that morning, walking to the ledge. Did she see the blush of the sky as the sun rose, casting the north wall of the canyon in gold and leaving the south in blue? Did she hear the hooves of the mules as they carried visitors to the bottom? Did she climb over the fence or go around it? Did she see how the juniper attaches to the rock, because that's in the nature of all living things – to cling to life and to the earth as if everything depended on it? Did she walk out onto that high limestone boulder? Did she sit for a while and take it all in? Did she cry?

The truth is that the timeline says she didn't make time for that. She was here, and she was gone.

And so I bring my daughter to this place, not to see where my mom ended her life, not because I think I'll find an answer, but to show her the beauty and the quiet, the arc of time, the way something as immutable as rock looks completely different in the shifting light, to witness the grand design of the world, to feel the forces older and stronger than the earth itself, and to accept the vastness of the things we cannot know.

Laura Trujillo and her husband and four children live in Ohio. Laura is a former reporter and editor who worked in the Southwest and Pacific Northwest. Now she works for a financial services company.

Editor's note: This story was written from a report from the U.S. Park Service, interviews with family members and experts, notes and the writer's memory. Dialogue in some parts of the story, such as with the ranger, was recorded in notes. Other dialogue has been recreated based on interviews and the writer's memory. The stepsister of the writer, when contacted about allegations of abuse about her father said, "That's not the man I knew."

But Why Are You Making Me to Get Mad What Have I Don Gwrong to You Baby Do You Want Tokill Me

Source: https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/surviving-suicide/2018/11/28/life-after-suicide-my-mom-killed-herself-grand-canyon-live/1527757002/

0 Response to "But Why Are You Making Me to Get Mad What Have I Don Gwrong to You Baby Do You Want Tokill Me"

Post a Comment